INNOVOTEK

A blog about the news of the latest technology developments, breaking technology news, Innovotek Latest news and information tutorials on how to.

State of Green Business: Supply chains go high tech

- Font size: Larger Smaller

- Hits: 11205

- 0 Comments

- Subscribe to this entry

- Bookmark

Whether the finished product is a smartphone, a shirt or a sapphire ring, tracing component parts back to their original sourceslong has proved an elusive quest.

Supply-chain sustainability hotspots vary widely from sector to sector. Deforestation is closely linked to food and consumer goods, while conflict minerals pervade the electronics, jewelry and automotive markets. But the lack of transparency and centralized systems to track products from inception to sale make the field ripe for disruption, particularly as consumers, investors and activists gain more awareness of the issues at hand — and make their concerns known to companies.

For individual businesses, the potential repercussions include operational, financial and reputational damage stemming from supply-chain dysfunction (or at least opacity). Combine those concerns with the increasing availability and affordability of advanced sensors, the global proliferation of mobile technology and increasing corporate reliance on cloud software systems. You get the supply-chain technology boom affecting industries across the board.

It may sound dull to dive into the details of convoluted global production routes, but make no mistake: The amount of money changing hands along a typical supply chain adds up to monumental sums. Transportation logistics alone is a nearly $5 trillion global industry. Manufacturing revenues top $11.5 trillion annually.

The first thing to understand about the rise of connected supply chains is just how many companies are vying for a slice of the market.

Some providers start with the basics, seeking new ways to vet individual suppliers and put that information online. Beyond that, there’s the push to better verify and communicate supplier data through secure digital channels. Others are more focused on better inventory management software, or using hardware to track products through the manufacturing process. At the end of the chain, a range of providers are honing new logistics offerings covering the last few miles of getting products to market.

The first thing to understand about the rise of connected supply chains is just how many companies are vying for a slice of the market.

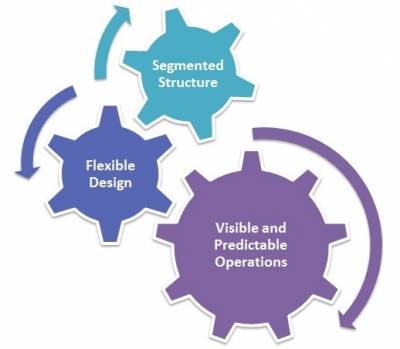

These efforts are propelled in large part by better understanding of risk management and the pursuit of supply-chain resilience. In other words, companies realize they need to be able to withstand unexpected shocks to any facet of a global business operation.

One area of increased company interest is the capability to respond to weather patterns made more volatile by climate change. The threat of superstorms and the potential downtime in their aftermath is pushing companies to seek advanced analytics for expected crop outputs to gird their commodity supplies, or to assess multiple delivery options amid changing weather conditions and fuel prices. Another area of focus is the more abstract idea of a "social license to operate," where a company’s ability to operate in a given region is jeopardized by local resistance.

"The next 10 years are going to see a level of change that is outside of our experience," said Volans founder John Elkington at a 2015 GreenBiz VERGE event on supply-chain transparency and traceability. "Part of our challenge, collectively, is to recognize those things early enough."

So, how does technology stand to help? Although business models in the supply-chain tech space differ, the new generation of technology and service providers are solving for two primary variables: efficiency and accountability.

The efficiency case is straightforward, usually involving a data-centric offering to better track natural-resource inputs. Beer giant Anheuser-Busch InBev, for example, is reaching back into its agricultural supply chain to experiment with sensors and software designed to maximize barley yields while minimizing water and fertilizer used in the process.

In the realm of accountability, companies such as EcoVadis are building a database of supplier report cards based on data points such as audit performance, major accident reports and other information available online — an endeavor that uses Big Data to build out more robust profiles than those afforded by old-school surveys or random inspections. Supply-chain labor and safety are two of the biggest liability concerns for companies. That has compelled providers such as LaborVoices and the nonprofit Good World Solutions to create tools for crowdsourcing real-time information on working conditions from laborers with access to cell phones.

Global networks encompass all manner of extractors, processors, intermediaries, manufacturers, packagers, shippers and more.

While data collection and analysis have gotten easier and more cost-effective, the scope of supply-chain sustainability challenges has gotten more difficult, with global networks encompassing all manner of extractors, processors, intermediaries, manufacturers, packagers, shippers and more.

This landscape looks likely to continue evolving quickly as production technologies and market trends such as additive manufacturing, robotics and urban agriculture improve. Some speculate that these innovations could combine with consumer forces, such as the trend toward locally produced goods, tore-localize commerce. For example, goods that were once shipped to Asia from Europe or North America for processing, then shipped back to consumers in those markets, instead would be handled regionally.

Today’s supply-chain cloud software and on-demand service providers aren’t the first to recognize the need to modernize the field. Over the years, supplier surveys and radio-frequency identification, or RFID, are two tools sold as ways to increase transparency and oversight. But their success has been limited, at least in terms of engendering wholesale transparency.

One reason is that countries regulate pollution and natural impacts very differently. Nagging challenges, such as reducing the burning of Indonesian forests to clear land for palm oil plantations, demonstrate that a cause du jour among consumers and activists in the Western world doesn’t always translate to immediate corrections upstream. International labor systems, meanwhile, vary widely in their ability to help the poorest secure better working conditions.

Some of them are just vaporware; some of them are driving real action.

Beyond that, there’s the issue of ensuring that new technologies actually work. What good is a fancy sensor if there’s no way to upload the information to the cloud from Dhaka or Dongguan?

"Some of them are just vaporware; some of them are driving real action," said Pierre-Francois Thaler, co-founder of EcoVadis. "It will take a long time before you can solve this problem just with technology."

While the array of supply-chain functions that stand to be re-ordered by technology can be a bit dizzying, the last part of the chain — the logistics of getting finished products to market — has become a particularly active breeding ground for innovation.

Just look at the upstart Cargomatic, which sells on-demand, short-haul trucking services. Flexe, meanwhile, operates an Airbnb-for-warehouse-space marketplace. Cloud Logistics offers services such as vendor-to-vendor communication, inventory tracking and other logistics data-analysis tools. All are part of the growing B-to-B sharing economy.

In this realm, too, the key selling point from a sustainability perspective is operational efficiency. Specifically, it can be more cost-effective to buy short-haul trucking or warehouse space as a service only when needed, rather than paying to purchase and maintain a bigger fleet or real estate portfolio.

If it all pans out, such technologies will help reduce fuel costs, waste and related emissions while keeping the wheels of commerce moving — literally — in an ever-changing world.